Climate Tucson: The Primordial Goo of Modern Living

You can say goodbye to gasoline, but petroleum isn't going anywhere fast

Take Two Petrochemicals and Call Me in the Morning

One in an occasional report on petrochemicals. Upcoming: PFAS in Tucson.

Read online at the Tucson Climate Report.

Ending our reliance on fossil fuels will take more than phasing out gas-guzzlers and flooding the grid with renewables. The world is awash in petrochemicals born of the decayed primordial plants and zooplankton oozing beneath us, crude oil.

Petrochemicals make plastic. In truth, no matter how good the recycling effort may be, at least for now, plastic is embedded in our lives. It’s like the atomic bomb. Once the atom was split, there was no turning back.

Here, the bomb is made of liquid methane from natural gas production and naphtha from the crude oil refining process. Combined, the goo is called "feedstock," the fossil-fueled womb for petrochemicals. At present, there are 84,000 petrochemicals on the FDA and EPA master list. Give or take.

While plastic represents about 10% of petroleum use, 99% of all plastic is made from petrochemicals. The same is true of pharmaceuticals. While drugs and medications as a category represent about 3% of petroleum usage, basically 99% of pharmaceuticals contain petrochemicals.

“What we’re seeing is a pivot in the oil and gas industry.”

Today, as the petroleum industry sees its market share shrink and renewables gain momentum (though far slower than we would like), the major global oil companies are looking at petrochemicals to fill upcoming profit and production gaps. An International Energy Agency (IEA) market analyst suggests that oil will peak as an energy industry “before the end of the decade."

British oil giant BP on its website projects that demand for oil will plateau “over the next 10 years or so before declining,” citing an expected drop in oil demand from heavy trucks that are more “efficient and are increasingly fueled by alternative energy sources.”

Plastic in its many forms is the best known and most pervasive petrochemical product, with nearly 9 billion tons manufactured since 1950. Fatih Birol, IEA executive director, says it’s “no understatement to say we live in a world dependent on chemicals.” Some deem petrochemicals “the building blocks of modern living.”

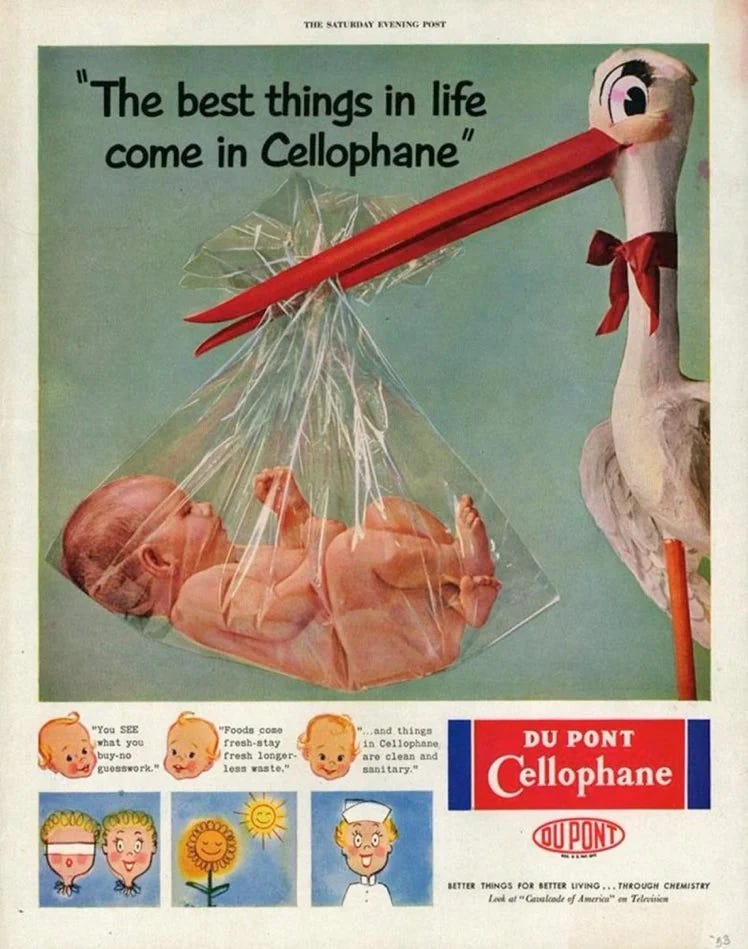

That statement is reminiscent of a memorable and long-running advertising campaign, pre-petrochemical, launched in 1935 by DuPont: “Better Things for Better Living ... Through Chemistry.”

The greater difference between now and then is that DuPont’s breakthrough plant-based Cellophane didn’t have ingredients like the notorious, ubiquitous “forever chemicals,” notably PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl), which have been detected in Tucson’s water.

However, DuPont’s Teflon product, which debuted in the 1950s, was made of PFAS and its own “non-stick” petrochemical, PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene). Over the years, DuPont dumped the chemical waste into the Ohio River. A $110 million settlement for the toxic spill was announced by the state of Ohio in the fall of 2023.

Adrienne Bloch, managing attorney with EarthJustice, an environmental nonprofit that represents communities burdened by polluting industries, including clients in Louisiana’s petroleum and petrochemical hub — the notorious “Cancer Alley” — underscores the irony of petrochemical’s ascension.

We can transition to clean energy, Bloch says, but with petrochemicals still in the mix “we are going to have the same negative climate impacts.” According to the IEA, petrochemical GHG emissions — in the U.S. approximately 286 million tons per year — will increase by more than 20 percent by 2030 and 55 percent by 2050.

The U.S. is a leader in plastic and petrochemical production.

“What we’re seeing is a pivot in the oil and gas industry” to the more lucrative petrochemical sector, says Bloch, adding that single-use plastic bags — a worst-case plastic product for the waste it generates — is the preferred go-to material for processing in the United States.

The U.S. is a leading petrochemical producer, estimated 2022 market size $49 billion, and it boasts four of the world’s 10 largest petrochemical companies, Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron and Marathon. The U.S. also holds claim to 40 percent of the world's ethane-based petrochemical production capacity.

Highly flammable, ethane, from natural gas, is a key ingredient in plastic.

The U.S. also excels in nurdles. Lentil-sized, never-die microplastics of all varieties, nurdles are used as starters in plastic manufacturing. These nurdle cocktails are toxic, a major pollutant of the world’s oceans and beaches and disturbing to comprehend en masse. One estimate of annual U.S. nurdle production: 60 billion pounds for domestic use and export.

Beyond plastic, petrochemicals are ubiquitous in powders and soaps, baby products, beauty products, hair products, cosmetics, human food, dog food, cat food, toys, tchotchkes galore, solar panels, EVs, fabrics, clothing, furnishings, a deck of cards, golf balls, lipstick. You name it, some part of it is likely petroleum derived.

Put another way, farm-raised salmon is pink only because of the petroleum-based synthetic red pigment, astaxanthin. Its purpose is to appease shoppers accustomed to wild-caught salmon’s pink meat, not the paleness of farmed fish.

Florida has a petrochemical all its own, Citrus Red #2, a food dye of the azobenzene family. Like salmon-colored salmon, it is used to make the state’s oranges, which tend to be green when ripe, orange and more palatable for consumers.

Considered “possibly carcinogenic to humans,” Citrus Red #2 is banned by the larger citrus-growing states, California and Arizona. By law, Citrus Red #2 can only be used to dye the peels, and the FDA requires signage identifying oranges from Florida.

Petrochemicals make expensive perfumes last longer and fancy face creams creamier. That new car smell is the aroma of leaching volatile organic compounds, VOCs, none of them worth breathing in.

Air-fresheners that dangle from rear view mirrors emit the most insidious of the petrochemicals, aromatics. The same is true of scented candles, incense and plug-in scent dispensers. The entire time the dispenser is working, chemicals are wafting in the room.

If the label lists “fragrance” or “parfum,” that refers to a trio of endocrine disrupters — parabens, phthalates, and/or synthetic musk — that “act like the hormone estrogen,” according to the Environmental Working Group (EWG), a consumer product watchdog. The FDA closely monitors aromatic and color-enhancing petrochemicals.

Then there are the pharmaceuticals and OTC drugs like aspirin, which contain the hydrocarbon benzene, also an ingredient in paint thinner and pesticides.

Petrochemicals are found in analgesics, antibiotics, antibacterials, suppositories, cough syrups . . . acetaminophen, in Tylenol, is a petrochemical. Novocaine is a petrochemical, as are sedatives, tranquilizers, decongestants, and antibacterial soaps.

Penicillin, a mold, is made up of petrochemicals like phenol and cumene. Phenol is a versatile petrochemical that, aside from medical uses, produces “slimicide,” an antimicrobial pesticide. The EPA considers phenol “quite toxic” if consumed on its own. The EU has banned its use in cosmetics.

Cumene, which is used to create phenol, is a “starting material” for manufacturing aspirin and penicillin — and also plays a role in gasoline blending and diesel fuel.

“Planet vs. Plastics”: This Year’s Earth Day Theme

There truly isn’t much we can do to rid the world of petrochemicals, if we wanted to. Some don’t. That doesn’t mean we can’t raise a fuss to make the future cleaner and advocate for green science. A study published this past April suggests there’s a credible way to make aspirin out of biomass. It’s a start.

The Earth Day organization is taking on plastic this year and rallying around the Global Plastic Treaty, which is demanding a 60% reduction in the production of all plastics by 2040. Sign the petition here.

Most everything about petrochemicals is up to consumers to learn. You won’t find them listed on labels, with a few exceptions. Get started by looking for the following preservatives, some problematic: benzoic acid, sodium benzoate, butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and TBHQ (tertiary-butyl hydroquinone).

Online Resources

EWG databases on cosmetics, tap water and pesticide safety. It includes a report on the state of Tucson’s water.

Search by brands, product type or ingredients using the Consumer Product Information Database.

The Chemicals of Concern database from the Campaign for Safe Cosmetics.

Safer Chemicals from the Environmental Defense Fund.

Testing for Contaminants in Food Products, also from the Environmental Defense Fund.